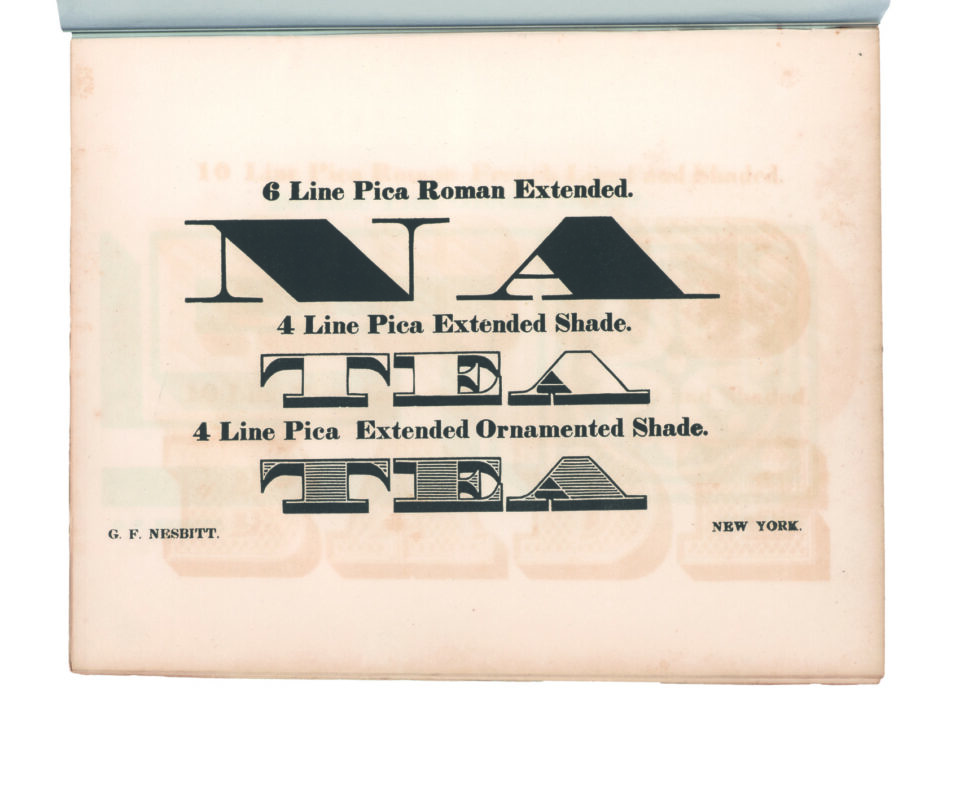

Roman Extended

6 Line

Box 013

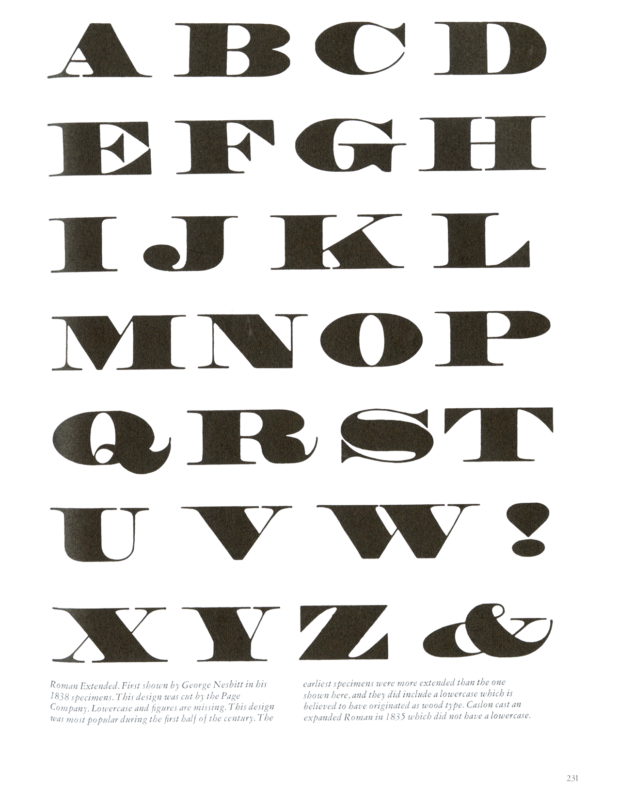

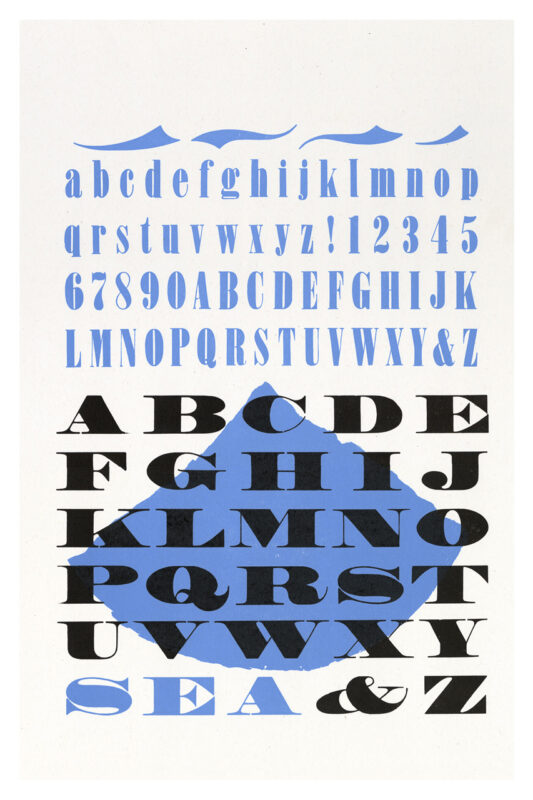

Roman | Fat Face | Uppercase

- This type measures 6 line in size and was produced with the end-cut method. The type block is stamped Page & Co., Greenville, Ct. which was used by Page and Basset between 1857–1859.

- This face was first shown as wood type by Edwin Allen in George Nesbitt’s 1838 First Premium Wood Types Cut by Machinery.

- This cut of Roman Extended was shown in American Wood Type on page 231 and in the folio on page 23.

Type name used by manufacturer:

Allen Roman Extended

Bill, Stark Roman Extended

Cooley Roman Extended

Knox Extended Roman

Morgans & Wilcox Roman Extended

Page Roman Extended [239]

Tubbs Roman Extended or No 2028

Wells Roman Extended [5151]

This is the Page cut.

Character Quantities

- A3

- B2

- C2

- D2

- E4

- F2

- G2

- H2

- I4

- J2

- K1

- L4

- M2

- N2

- O1

- P2

- Q1

- R2

- S4

- T2

- U2

- V2

- W2

- X1

- Y2

- Z1

- a-

- b-

- c-

- d-

- e-

- f-

- g-

- h-

- i-

- j-

- k-

- l-

- m-

- n-

- o-

- p-

- q-

- r-

- s-

- t-

- u-

- v-

- w-

- x-

- y-

- z-

- 0-

- 1-

- 2-

- 3-

- 4-

- 5-

- 6-

- 7-

- 8-

- 9-

- &1

- $-

- !2

- Open Apos/Comma2

- Close Apos1

- Period4

- Question Mark-

- Colon-

- Semi-Colon1

- Dash1

- Ligature-

- Other-