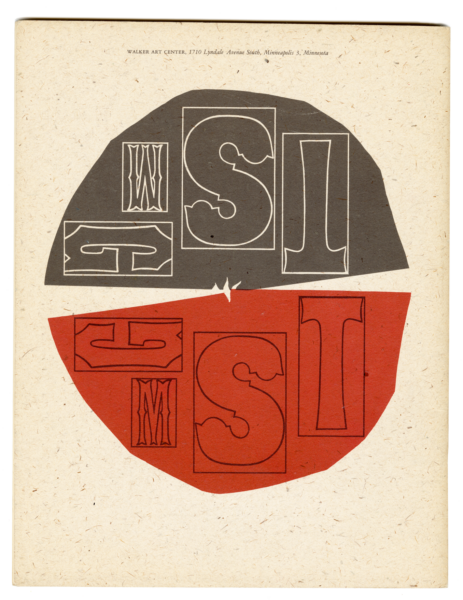

What is Wood Type?

Let’s cover the basics of what the RRK is all about.

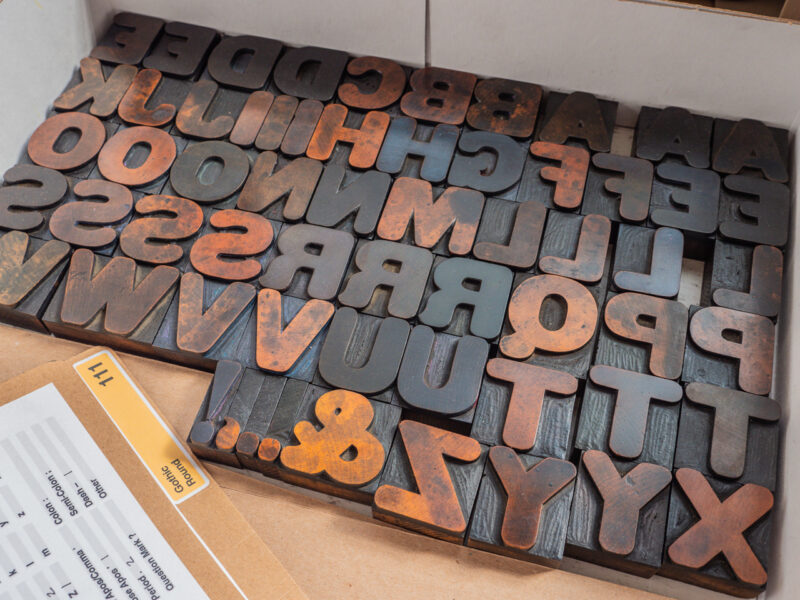

Wood Type is a form of moveable type utilized in letterpress printing. Each of the 166 typesets in the collection features a box of individual blocks for each letter and punctuation mark. The characters are assembled into a desired composition.

Letterpress printing is a relief printing process, which involves a surface being coated with a layer of ink and then pressed onto a substrate (i.e paper, fabric, or wood). Typically, relief printing involves a carved surface, where material is removed so that a shape or image stands out from the background of its material. The raised portion collects ink, and then is pressed into a surface.

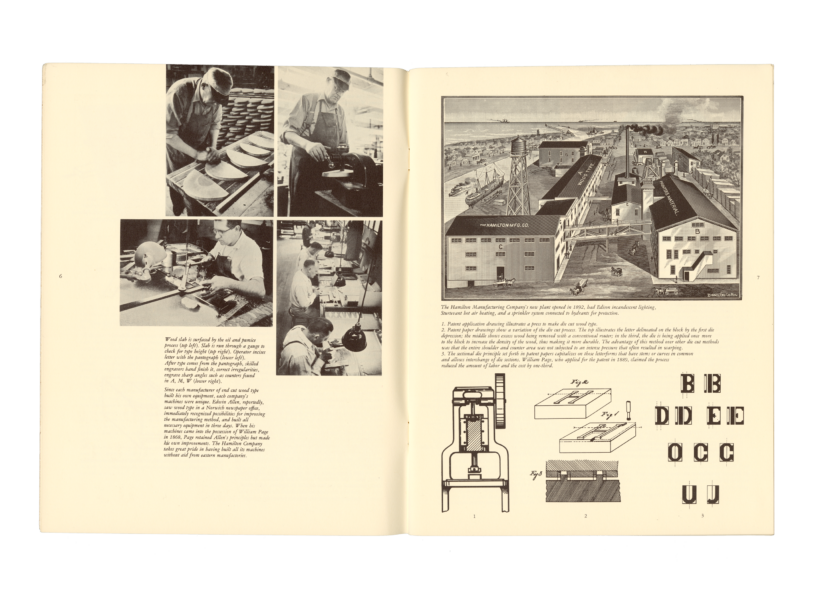

American wood type is carved from end-grain maple wood, an extremely strong and durable material that has allowed the type in the collection to remain in use since the 1800s—some pieces in the collection are approaching 200 years old. Wood was lighter and cheaper than cast metal, which previously had been the sole method of producing type for printing. As letterpress printing boomed in the mid-1800s, the wood type industry flourished with it.

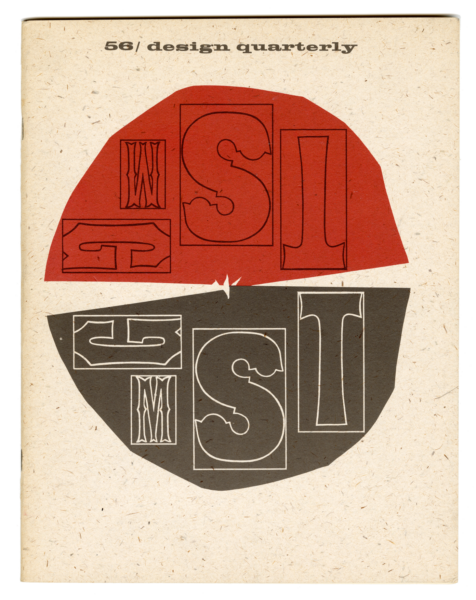

The legacy of wood type is fundamental to contemporary graphic design, and how we think about conventions of typography today. Wood type design and technical standards have gone on to inform how we utilize contemporary tools to do this same work.

As a result, we uphold the collection as a key resource in our curriculum at the School of Design & Creative Technologies. All our students, across all design disciplines, are hands-on with wood type at some point in their academic career. We view the RRK as an essential connection to the lineage of graphic design, as we learn both historical and contemporary processes and techniques.

Type Production

Wood was an effective material for making type at larger sizes for display poster purposes, because it was readily available, cost-effective, lightweight, and durable. But prior to 1800, nearly all European and American letterpress printing was done with metal type. Typefounders could rapidly cast thousands of identical lead-alloy sorts (glyphs or characters) using a type mold, which was a very effective technology for casting type at small point sizes. However, larger sorts took a long time to cool in the type mold, which slowed down the pace of production. Thus English typefounder Thomas Cotterell turned to sand-casting to produce the unprecedentedly large, two-inch-high letters that he began selling c.1765.

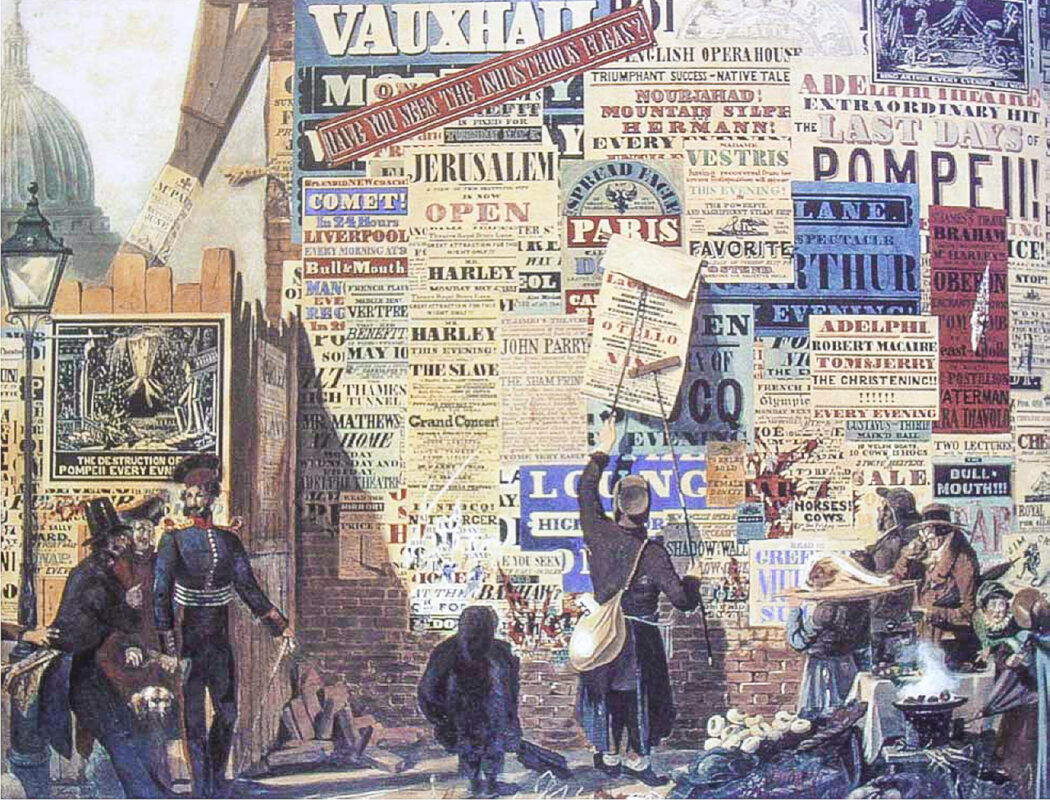

Although Cotterell’s typeface was enormous for its time, the same typefaces that looked very large when printed in books or on handbills were not large enough to suit the needs of nineteenth-century manufacturers, entertainers, retailers, and governments. These groups increasingly used posted notices (aka posters) to communicate with literate, urban mass audiences. To catch the eyes of passersby walking or riding through busy city streets, printers needed type even larger than Cottrell’s.

In the 1820s, hand-cut wood type provided a solution, but a slow and therefore relatively expensive one. However, Darius Wells’s invention of the lateral router in 1827—which his fellow American William Leavenworth paired with a pantograph in 1834—made it possible for the first time to quickly resize and replicate type in wood. The eclecticism and exuberance typical of mid-nineteenth-century posters and handbills is due in large part to the availability and affordability of so many styles and sizes of wood type.

Manufacturers used four different processes to commercially produce wood type: router-cutting, die-cutting, veneering, and celluloid or enamel facing. The RRK includes examples of type produced by the first three methods, but not the fourth.

Visit

TYPE TOOLS

for more info & resources

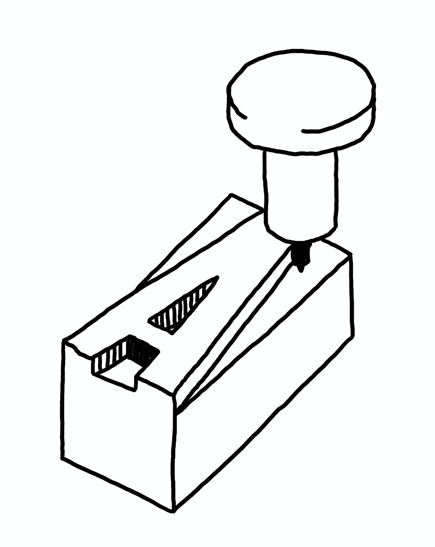

The Router-Cut Method

All manufacturers used the router-cut method to produce wood type. This method consisted of spinning a metal cuting bit at high speeds to remove (or rout) material from the face of a type-high block of hardwood, while tracing around a positive printing shape (a letter’s contour) to produce the negative nonprinting area. This same basic machine, a router, is still used to mill and shape a range of materials and is nolonger limited to just wood. In the Design Lab, we use a small CNC (Computer Numerical Control) router to cut printing blocks from vector images.

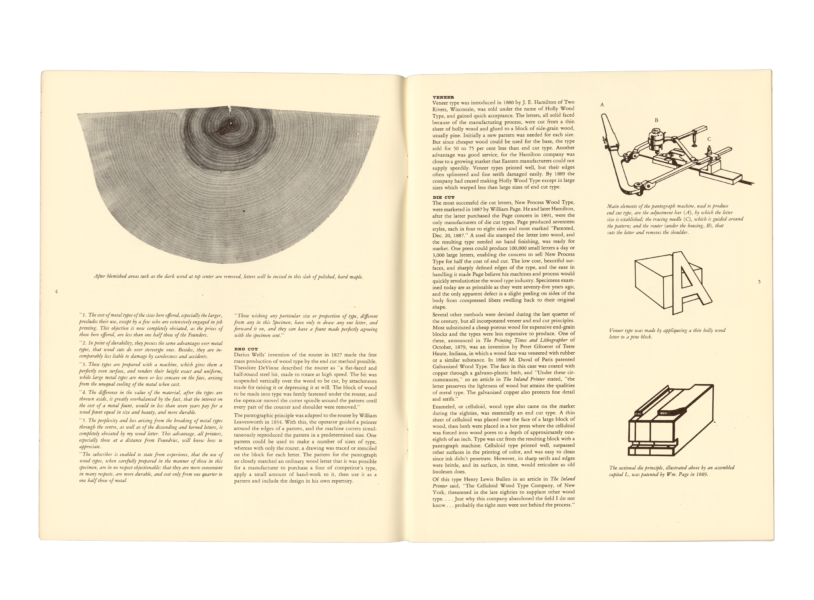

In 1834, William Leavenworth and A.R. Gilmore in Syracuse, New York, adapted the pantograph—a sixteenth-century device used to mechanically duplicate line drawings—combined it with Wells’s lateral router to cut wood type forms. This technique is referred to simply as the router-pantograph method, and allowed for the mechanical mass-production of wood type. Further, by manipulating the articulation of the pantograph’s arm, the machine could be used to alter the letterforms from full-face characters to condensed and expanded characters.

The removal of the router’s artifacts required skilled handfinishing using traditional wood engraving tools to create sharp angles where the router left rounded corners when cutting at a non-reflex angle. The router-pantograph was originally powered by a foot treadle but was quickly adapted to steam power, and then eventually to electrical power, further accelerating wood type production. This efficiency provided through the use of the router-pantograph made it possible to develop and produce new wood type designs more quickly and easily than it took a type founder to develop and produce metal type, and at a fraction of the cost. The combined router-pantograph was used to produce wood type across the entire duration of the industry.

The Die-Cut Method

The die-cut method consisted of stamping a type-high block of hardwood with a thin steel punch fashioned to match the contour of the letter. Early versions of this method required the type be finished by hand, since it was necessary to remove the remaining wood left in the negative area around the contour. Later refinements finished the entire letter with one stamping.

The die-cut types were produced by the William H. Page Wood Type Co. Precursors to the die-cut method were developed sometime after 1828. T.L. DeVinne recorded the improvements to the tools used by Wells in conjunction with the router, including the use of patterns made of brass sheet instead of hand-cut cardboard patterns and “cast-brass patterns, with elevated edges, which when pressed in the wood, both marked and engraved the outlines of each type.” This seems to clearly describe the basic components of the die-cut method. In 1852, John McCreary filed for a patent on a die-cut process; the patent—U.S. Letters Patent No 9,454, issued December 7, 1852—described many facets of the method later used by William Page in 1887.

George Setchell entered into business with William Page in 1881. Together they patented improvements to the die-cut production method between 1887 and 1889, largely to counter the price competition from Hamilton’s Holly Wood Type. In 1889, Setchell sold his interest in the William H. Page Wood Type Co. to Samuel Dauchy. Dauchy became president of the company and oversaw the acquisition by Hamilton Mfg. Co. in 1891. After the acquisition of the William H. Page Wood Type Co. in 1891, Hamilton continued using this method until around 1906.

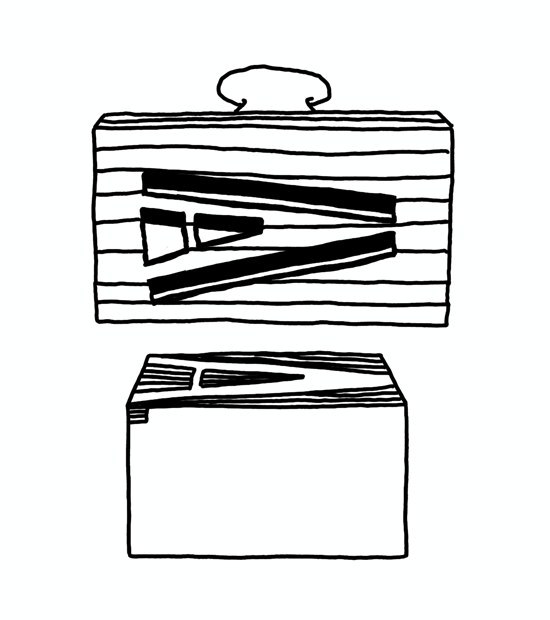

The Veneer Method

The veneer types were produced exclusively by the Hamilton Manufacturing Company. J.E. Hamilton invented the process in 1880, in Two Rivers, Wisconsin. Cutting the letter design from a thin piece of holly wood, the letter was then affixed to a wood block. This was sanded and polished on the printing side, after which the back was planed to bring the block down to type-high. At the time, this was a major innovation in wood type production, allowing Hamilton to sell his Holly Wood types at half the cost of his competition, who were producing wood type with the combined router/pantograph.

This less expensive production method gave Hamilton an economic advantage over his competitors. The Hamilton Mfg. Co. was able to acquire all of its major competition, including Page, Morgans & Wilcox, and Heber Wells, during the 1890s. Tubbs & Co., the last major competitor from the nineteenth century, was acquired in 1918. Hamilton added the end-cut method to their production in 1888, and phased out use of the veneer method around 1890. After the acquisition of the William H. Page Wood Type Co. in 1891, Hamilton gained the machinery to produce type with the die-cut method. They continued using this method until around 1906.

Celluloid / Enameled Method

Celluloid type was produced by either fusing the wood block with celluloid then routing through the coated surface and wood together, or die-cutting and hot-pressing a layer of celluloid into the surface of a wood block to cut the letter and seal the surface simultaneously.

Kelly described this process in American Wood Type, but the collection lacks examples of type made by this method.